Over 12 days into the trip and instruments are being recovered fast and furiously. We are just finishing the densest of the 3 lines and at one point we were pulling in a station every 6 hours, working 24 hours around the clock. The transit from L20D to S19D marked half-way and we have crossed the equator twice already, hopping back and forth between the Nubian (Africa) and the South American plates. We will soon make it to S17D, our deepest station, which lies in over 5.2km of water. The OBMT will take well over 4 hours to rise to the surface at this station.

Over 12 days into the trip and instruments are being recovered fast and furiously. We are just finishing the densest of the 3 lines and at one point we were pulling in a station every 6 hours, working 24 hours around the clock. The transit from L20D to S19D marked half-way and we have crossed the equator twice already, hopping back and forth between the Nubian (Africa) and the South American plates. We will soon make it to S17D, our deepest station, which lies in over 5.2km of water. The OBMT will take well over 4 hours to rise to the surface at this station.

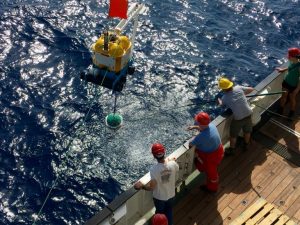

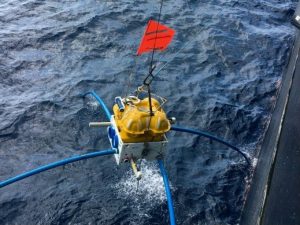

Finding an instrument when it pops up at the surface can be a bit of an adventure. All instruments are fitted with a bright orange flag, a strobe light and some sort of radio communication that indicates it is on the surface. And, the transducer can be used to monitor the distance to the instrument as it rises. Despite all this, things can go wrong. We have had instruments  where the strobe light fails to turn on, which makes instrument location in the dark a real challenge. The radio or transducer can be used to get a rough estimate of range and the ship then tries to triangulate based on measurements in a few locations. The ship has good search lights and the Bridge has some night-vision goggles. In the daytime, everyone looks for the red flag on the instruments, but even this can be difficult if it drifts a long way. The worst scenario is radio failure, a broken strobe and a snapped off flag – fortunately we have not experienced this. The OBMT is this easiest to find as it also has a GPS locator on it. If an OBS and OBMT rise at similar times, we always go for the OBS first. The ship’s crew are amazingly eagle-eyed and are usually the first to spot the instrument from the Bridge. Pictured is a Lamont OBS coming on board just as the sun is rising at 6.30am.

where the strobe light fails to turn on, which makes instrument location in the dark a real challenge. The radio or transducer can be used to get a rough estimate of range and the ship then tries to triangulate based on measurements in a few locations. The ship has good search lights and the Bridge has some night-vision goggles. In the daytime, everyone looks for the red flag on the instruments, but even this can be difficult if it drifts a long way. The worst scenario is radio failure, a broken strobe and a snapped off flag – fortunately we have not experienced this. The OBMT is this easiest to find as it also has a GPS locator on it. If an OBS and OBMT rise at similar times, we always go for the OBS first. The ship’s crew are amazingly eagle-eyed and are usually the first to spot the instrument from the Bridge. Pictured is a Lamont OBS coming on board just as the sun is rising at 6.30am.

Communication during station retrieval is crucial, and each group – the Bridge, deck crew, main lab (picture below), OBS lab and OBMT lab – has a walkie-talkie. The Bridge makes all decisions about the ship and the use of its equipment. The main lab decides things like the order of pickup, when to turn on and off the swath bathymetry and to what depth the SVP (sound velocity profile) is conducted. Our cruise is a bit unusual in that we have both OBS and OBMT instruments at each station. It took us a few stations to iron out the bugs and to develop a standard procedure for recovery, which is slightly different from the previous blog:

Communication during station retrieval is crucial, and each group – the Bridge, deck crew, main lab (picture below), OBS lab and OBMT lab – has a walkie-talkie. The Bridge makes all decisions about the ship and the use of its equipment. The main lab decides things like the order of pickup, when to turn on and off the swath bathymetry and to what depth the SVP (sound velocity profile) is conducted. Our cruise is a bit unusual in that we have both OBS and OBMT instruments at each station. It took us a few stations to iron out the bugs and to develop a standard procedure for recovery, which is slightly different from the previous blog:

- When we arrive at the area, the ship moves into hold on the edge of a circle centred on the drop position of the OBS and with a diameter equivalent to the water depth. The ship lowers a keel with the hull transducer in it (this ensures clear acoustic communication with the instruments).

- The OBMT guys establish contact with their instruments, often even before we get to the circle. They then send a signal to release the instrument (a burn wire holds the instrument to the anchor). They confirm lift off, establish an ETA and then disable communication.

- Next the OBS team establishes contact with their instrument.

- A 270-degree circle is sailed around the circle, ranging to the instrument. The OBS location is later established using simple triangulation and knowledge of the sound-speed of the water column.

- When finished, the ship holds in ‘Dynamic Position’ or DP, whilst the OBS is released from the bottom. An ETA at the surface is calculated.

Once it is confirmed that both instruments are rising, a Sound Velocity Profile (SVP) is taken. This measures the P-wave velocity and the temperature of the water as a function of depth and takes anywhere from 30 mins (for 700m) to 90 mins for our deepest SVP, which is 2.5 km. Here is a picture of the SVP logger being brought on board as the sun rises – it is attached to a 500 kg weight that looks like a giant bath plug.

Once it is confirmed that both instruments are rising, a Sound Velocity Profile (SVP) is taken. This measures the P-wave velocity and the temperature of the water as a function of depth and takes anywhere from 30 mins (for 700m) to 90 mins for our deepest SVP, which is 2.5 km. Here is a picture of the SVP logger being brought on board as the sun rises – it is attached to a 500 kg weight that looks like a giant bath plug.- The ship then sails to the estimated position that the OBS will pop up.

- The OBS is retrieved.

- Then the ship sails to the estimated surface position of the OBMT, where it is retrieved.

- The drop-keel is raised, the swath bathymetry is turned on and the ship sets a course for the next station.Sometimes the instruments are recovered but then have data problems. Thus far, we have seen a flooded seismic sensor, a ruptured battery cable, a frozen gimbal that stopped the seismic masses releasing, and two data logger failures. We are pushing technology to the limit. It is a bit like leaving your computer on at home unmonitored to record something for a year – but, only using batteries for power and at the bottom of the ocean where pressures are 500 times that on the surface.